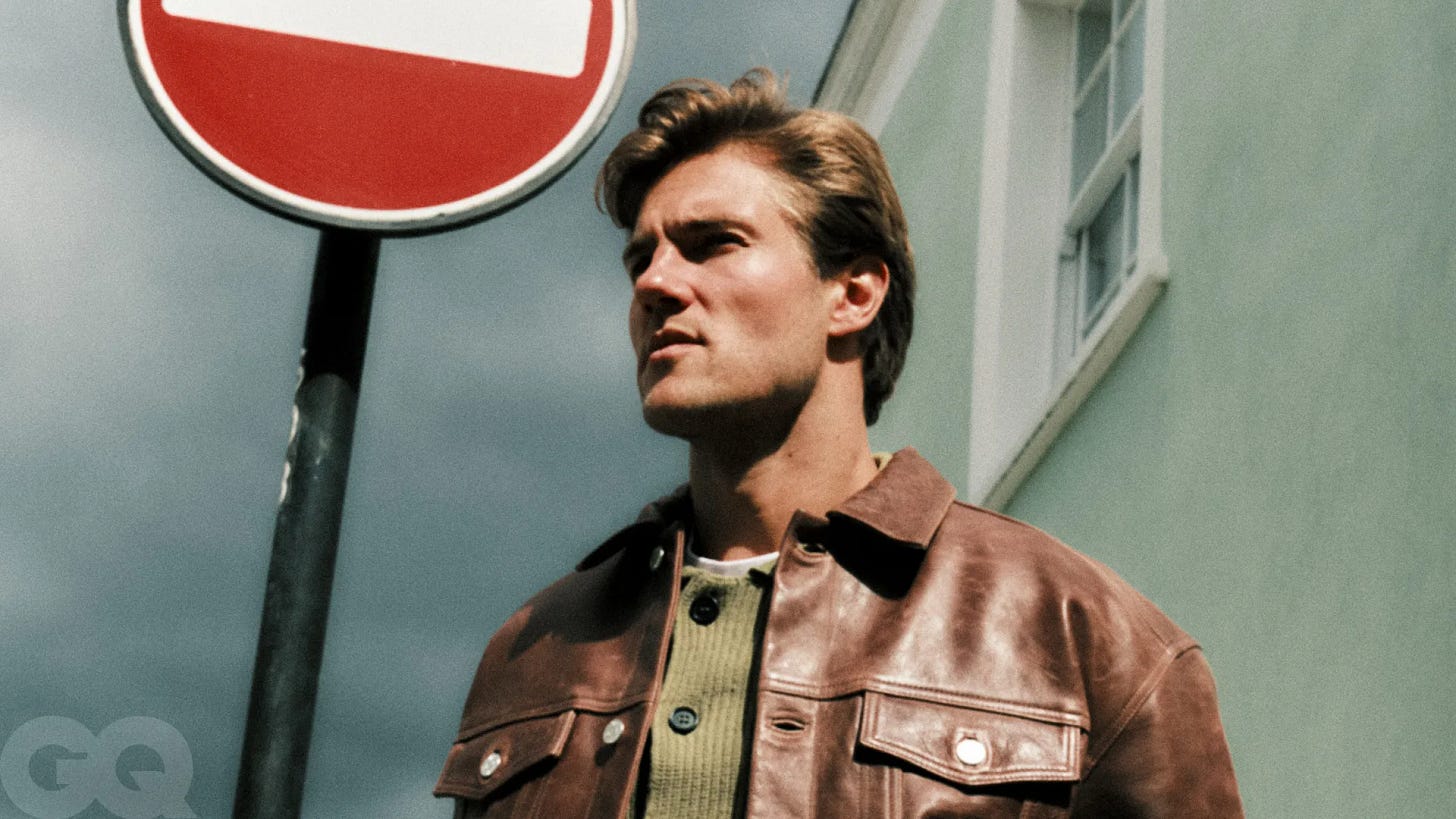

Last Friday, the second in my series of profiles-with-stylish-footballers came out. This time, it was me profiling Joachim Andersen — Crystal Palace’s big handsome beefcake of a centre-half.

We spoke almost nothing about football. He hates talking about football and, given my day job, talking about football until my jaw aches, I was happy to oblige.

Instead we talked about “lifestyle” — something he has a very nice one of. We spoke about getting dressed up for dinner, brands he liked, his ideal level of famousness, with him admitting that (on his way to living what might just be the perfect life) he has had some “helping hands” (the handsome middle class son from a handsome middle class suburb with a father who is a serial entrepreneur and, in Joachim’s words, “like me, but less handsome”) as well as the fact him and a bunch of the more discerning Palace players have a Whatsapp group about coffee called ‘Coffee Talk’.

Anyway, the piece came out pretty nicely I think and was warmly received by the club’s fans and interested-in-the-words-of-large-blonde-men neutrals. I was happy. He was happy. We’re all happy.

But what I was most interested in was creating a voice in the piece that felt distinct. Joachim’s own voice is as you’d expect — deep, resonant, dryly humorous in that Scandi way where sometimes you’re not sure if they’re mad at you — but it wasn’t the voice I wanted for the piece.

When approaching a piece like this — talking to a famous person about subjects which many would consider superficial at best — I like to work out their energy, and have that shine through the words. That doesn’t mean it is a perfect reflection of the person — I’m usually only with the subject for a couple hours and you can’t know anyone in that time, and can we ever really know anyone? — but a reflection of the energy I felt around them.

Let me show you what I mean.

Joachim’s energy is level, calm, with a crinkly-eyed smile quality, but quiet. The voice I took for the piece upped the intensity, upping the energy, making it even a little silly in places. I wanted to reflect the lack of self-seriousness Joachim cultivated, even as his facade was icy cool. His interests were folly, not introspection, and so the voice followed suit: I followed that folly and had a lovely time with it, throwing colour at the walls, and getting liberal with my use of parentheses with excitement, adding breathless asides to reflect my interpretation of the world he was parcelling out to me. I was happy when I met Joa and he seemed happy, too, so the piece had to be jolly in turn. It was a voice that wasn’t his nor even mine, but what happened when I tried to blend the two with the energy that joined us in the room(s) we shared.

The previous piece in the series — with Spurs winger Brennan Johnson — was quite different in tone. The piece was more structured, more dramatic. I met Brennan in a malaise of my own: It was mid-February and dreary. I cycled to the shoot on the cold afternoon of a drizzly Valentine’s Day and Brennan, deep into a difficult first season with a new club, was warm, friendly, but ultimately a little pensive, maybe even maudlin. The piece reflected our combination of moods. How could it not? He struck me as a man who was often given to brooding after a match, when the high anxiety of a game stops suddenly and he is left with the wreckage to pick through on his own. This quality was felt in the room as we spoke after the shoot, his energy lowered, maybe a little tiredness creeping in. We looked back. We got nostalgic. The voice I chose in the piece had that in mind: He was looking for something, and so was the piece. ‘Perspective’ was what I called it. The voice — and the piece — was hopeful and understanding (I think, anyway) and I felt that was the energy we shared together.

Joachim seemed to be searching for nothing. He had everything he wanted. The piece reflected that. Brennan did not. So I reflected that, too.

Here’s a brief break: Want to ask me a question about writing, storytelling, or something else? Just reply to this email. I’ll probably make it into an upcoming newsletter.

Anyway, back to it.

I think of it like how actors love to wax lyrical about the magic of theatre. What makes it special, they say, is the way the words and the staging are the same and yet every performance is different. What happens to you on the way to the theatre is as important to characterisation that night as anything “a director” might point you towards.

There’s a school of thought that you shouldn’t bring yourself into your writing. That style is getting yourself out of the way of the words, rather than finding yourself through them. I’m sure there are cases when that is true — I don’t care how shitty a courtroom reporter’s day was, sorry — but so much of profile writing is about empathy for a person you have never met before, and will likely never meet again.

Wright Thompson — my guy — has written about how he approaches profiles. I’ve quoted it here before, so I’ll paraphrase: He enters every profile trying to work out their common ground. With Michael Jordan, he found an icon at an impasse, aged 50 and still mourning his father, just as Wright — though younger, and an icon to me at least — was, too. How could what he wrote not be a story of sons and their fathers’ shadow?

What I’m writing is usually… Not that deep. But often I’ll work with newer writers on understanding their unique place in the words they commit to Google Docs.

I never studied writing, but I learned the hard way — writing a load of terrible shit until it got less terrible, a metric I quantified by the amount of comments [God, remember comment sections?] saying things like ‘This cunt is a cunt’ and ‘This is, I guess, one of the better structured Year 7 essays I’ve ever read’ — until writing became something like fun.

It became fun because I was understanding myself through it. Didion’s “'I write entirely to find out what I'm thinking, what I'm looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear” feels a little too lofty, but I found my voice through the voice of others.

When I started writing, I was a fucking clepto. I was terrified I had no interesting opinions or life experiences and would be doomed to writing product copy for white T-shirts made by children and sold to the dumbest adults in the world and so, I stole.

It’s what every writer does at the beginning, or if not, they should do:

You write. It’s bad. So you read and read and read. And you take a little of that voice, a little of that one and this one. And it’s still bad but… Less so. You feel like you’re getting somewhere. You keep stealing, keep reading, keep writing, adding more and more voices to the unholy gumbo on the page until, one day. Well, it’s still bad but you like it. Liking it is important. If you’re beating yourself up, you need to go get a breather — pop to the shops, drink a Diet Coke, circle the block — and come again. As soon as you start to read your work out loud – like, actually out loud, with your actual voice — you start to understand which words feel like yours, and which ones definitely do not. Now you’re ready to begin.

Once you understand your voice well enough, you can refract it through others. You can have each new experience colour your writing. Your voice can bend and twist and stretch. It won’t break if you keep reading it out loud, making sure that it still feels — even just a little bit — like you.

I keep it feeling like them by recording their voice and listening to it while I’m doing stuff like going to the shop to buy pre-cooked prawns for this nice little prawn-mango-avocado salad thing I’ve been enjoying lately. As soon as I start to hear their voice in my head, I know I’m there. Sometimes I’ll sit down — salad finished, delicious — and when cherry-picking their best quotes from the interview, I’ll open up another window and write a few totally random sentences exactly in the cadence, rhythm, and syntax of their voice. All of the texture and irregularities, the you knows and rights and ums. And then I swallow it whole, delete that document, and go back to my work.

It’s a weird one — writing about them to write about yourself. But we write to understand others, and that understanding turns into learning, and by learning we improve the measure of our own ability to communicate.

Seeing writing as a way to converse with people — in the words of Jonathan Franzen who is both brilliant and, definitely, a total wanker: “The reader is a friend, not an adversary, not a spectator” — by being yourself is the only way I know how to make things make sense. There is no perfect truth. True documentary doesn’t exist. So I lean into that, and present my side.

Neither of those GQ pieces are perfect, although I’m certainly pleased with how they’ve both turned out. (And so are my editors, which is handy.) I’m always trying to explore new ways to approach assignments such as this, and I wanted to relay how I got to a place where I got from “This is a challenge” to “I am happy with the result”.

I think to get there I always ask myself: How can I make this person that the reader has never met and who — until like two weeks ago — you had never met feel like a real, well-rounded person on the page?

It’s not in the quotes, not really. People make a big deal about the art of interviewing but those answers can only inform your point of view; they won’t write the piece for you. You’re often asking people to articulate thoughts and feelings they rarely have the solution to. The efficacy in that storytelling, I think, as a writer, is in finding a way to express the feeling around their words with your own.

Joachim and Brennan are footballers. That’s their job. This is mine.

That’s what voice does in a piece. It brings a story to life.

Sam I really look forward to your writing. Thank you for putting it out there for us

Loved every word of this Sam - good to have access to your mind