Welcome back. We’ve got the second part my interview with Ted Philipakos coming up on Thursday. The response to the first part was amazing. Thanks to everyone who shared.

Essay club’s up and running, in case you missed it. All you have to do is read the article linked here, do some thinking about it, and wait for my email on March 19th. Then we’ll all talk about it in the comments. It’s a piece of piss, really.

Anyway, today’s ‘sletter is definitely linked to that. I’ve been busy reporting on a couple of great projects — a few magazine profiles, and another, longer project quite unlike anything I’ve ever done before — and, as always, was out looking for inspiration. I think I found it.

Chat soon,

Sam

“I’m outlining on the road during stories. I’m outlining constantly. Trying to figure out: What is the story? What is the story? That’s what I’m asking myself over, over and over again on the road. What’s the story? What’s the conflict? What’s the resolution? What’s the arc? What’s the narrative arc? What question are you going to ask at the beginning that you answer at the end? What’s the end? I like ends, I like hammers. I want the ending that kind of makes you sort of feel hollow briefly in your gut.” — Wright Thompson

There’s something terrifying about reporting that I’ve never been able to put my finger on. For years I was a desk writer, too nervous to talk to people in the street around me, too skint to travel to far flung places where my inane questions would, at least, be submersed in total anonymity.

I think the difficult, scary thing about it is the thing that makes it most exciting: You often don’t know what you have until you find it. If you go in looking for it, you’ll kill it. You have to come at it slowly, with open arms, with empathy, with your head on the swivel. But what I didn’t know is when to stop talking.

I’m a nervous talker. I’m also a nervous laugher, which often comes at inappropriate times and infuriates people around me. But this exciting, longer, different project I alluded to above — god, I’m so fucking mysterious, man — is an audio documentary — less mysterious now, but trust me — and meant I had to, in industry terms, shut up and listen.

My nervous talking, nervous laughing, my constant verbal affirmations — grunts really; mms and nnhs, trying to urge the speaker on, letting them know that I am listening, that I am present — just didn’t cut it. It was literally ruining the work. And something clicked for me. Do less. Do far less. Do more in the background, of course. Before you meet, read everything, write every note, think every thought, and then forget it. Let what you learn be muscle memory. The first few interviews I did, I was so eager to share what I learned, that I blurted out everything, all my well-reasoned, well-written thoughts. My interviewees kinda sat there and said, ‘Well… yes.’

I was right, but I was doing it wrong. I wasn’t listening. I wasn’t learning. I had to learn to leave space. To let them answer. Because you’re there to learn about them, after all. And only by learning about them, will you learn more about you.“Think about the central struggle in the life and go find a character that you imagine is dealing with those things.” — Wright Thompson, on the art of the profile

[Unrelated, really: I just love Patsy Cline.]

Checking my search history, here’s a reminder to myself some things I’ve recently become obsessed with:

Psychographics, ambient jungle that sounds like the soundtrack to a PSOne game, Cord Jefferson, Jeffrey Wright, Wright Thompson, the politics behind the 1980s’ hard-body movie subgenre, alternatives to DocuSign, Larry Gagosian, ‘aggro-rithms’, retired Colombian midfielder Fredy Guarín.

Every writer I know develops these kinds of fleeting infatuations with subjects. But on a thematic level, every writer has an underlying preoccupation. After finding your voice, working out which writers you should/should not steal from, and how to properly create and repeatedly chase an invoice, understanding what your preoccupation is might be the most important thing a young writer can learn. It’s usually a question, one which — no matter what you’re writing about — can be read somewhere in the code.

I think I finally worked out mine, after nearly a decade of throwing words together on a screen to see what fits:

Why are young men so weird? And what happens to these young men when they’re not young anymore?

Under my window a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look downTill his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade,

Just like his old man.My grandfather could cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toners bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, digging down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

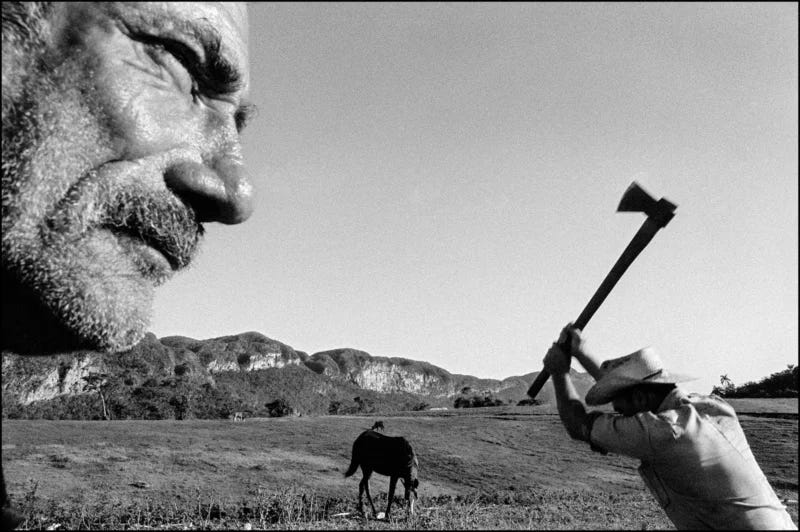

— from ‘Digging’ by Seamus HeaneyFriends fear he’s talking about poetry again. I’ve always had a curious relationship with this Heaney poem. The imagery has always been so bold, so right, the relationship between his father and his father’s father so clear, their lineage shared in the fine, honoured masculine tradition of digging a big fucking hole and then gazing into it, seeing something beyond themselves, beyond sod, beyond potatoes and blackness.

But at the start and end of the poem, ugliness. I always lop them off whenevr quoting it. Something uncouth, kinda gross, ruining the magic that I felt.

It begins:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; as snug as a gun.

It ends:

The cold smell of potato mold, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But Ive no spade to follow men like them.Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

Ill dig with it.

Hate hate hate it. Even quoting it here angers me greatly. There’s a kind of cloying smugness to the ‘my pen is my spade’ imagery that makes me feel honestly quite sick. Perhaps it speaks to my own class insecurity, a guilt maybe, about my chosen profession — sending emails, talking on Zoom, saying things in meetings like ‘I think we need to approach the strategy quite holistically’. But now that I have slapped these words in juxtaposition with what I’ve written just before it, I see something different.

You don’t need to be in the poem, Seamus. You are in there already, in the tension of your father’s act, in the melodrama and the diffidence of the observations, the word choice. There is an underlying shame in Heaney’s choices that ache something you don’t need to mention directly. It is there, it is always there, because the stories we choose are always about us, after all.“When you’re a kid you think writing has to do with words and then you figure out that it doesn’t and that it has to do with structure. It’s architecture. That’s the whole job. It has nothing to do with words, really. It’s outlining, structure. It’s conflict and resolution.” — Wright Thompson

I came across the word of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Brady Dennis, and the 300-word stories reporting about real people in Florida. Every ounce of fat was cut away. Every word mattered. They were well-reported, colourful, characterful. He won the 2006 Ernie Pyle Award for his 300-word missives.

“I learned it doesn't take 3,000 words to put together a beginning, middle and end,” he says. “A good story is a good story, no matter the length. And sometimes the shorter ones turn out [to be] more powerful than the windy ones.”They were personal and universal, the best kind of writing. Telling the stories of great (and often not-so-great) systems through the lives on individuals1. As the footnote fans will see, it’s a style of writing that has a long lineage in literary journalism. But it remains a uniquely American form. Not until I began reading Aniefiok Ekpoudom’s excellent book Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope in Modern Britain, a character-led portrait of British music and idenity, did I realise how little of it happened on these shores.

There’s an element of self-mythologising to America which builds appetite for grand narratives unfurling from tiny acorns. Maybe the British are too shy for that. Either way, I feel like a return to people-led storytelling would be a welcome relief for a media landscape that is, right now, at best dreary or, at worst, dead.

Not all portraits need to follow long and winding roads. Lives themselves are complicated, messy, and do not follow the narrative arcs that writing must adhere to. But we can see scenes within them which resonate. Dennis is one example, but I wanted to give two others quite different in their execution:Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browserFirst up, we’ve got Hunter Prosper. A nurse turned demigod to TikTok storytellers, the format couldn’t be simpler: a camera points at a person, an emotive prompt is given, and what follows is an honest, heartfelt story that transcends the medium. At its best, it has made me cry my little eyes out. At the moment, they’re pivoting to interviewing celebrities, which is a shame. That is far less interesting that the unguarded thoughts and feelings of regular people — usually old people, further solidifying the Wise, Old, Oyster-Eyed Sage trope which, for me, never misses.

It makes me think back to something I read from Brady Dennis, talking about his 300-word portraits of people he stumbled across in the street: “The easiest thing was my complete confidence in the people we would find. I believe that each person not only has a story to tell, but that each person has a story that matters. I’ve always felt humbled in the presence of everyday, ‘ordinary’ people who are willing to share their lives with us.”

My second example, follows a similar vein: It’s that ol’ Instagram mainstay Humans Of New York. Relegated to the kind of stocking-filler fodder found near the counter of your local Urban Outfitters, what has made HONY such an enduring success is its simplicity. It is the story of humanity as it relates to New York, a place both teeming with life and desperate to squeeze life out of its citizens.

At the time of writing, 13 million people follow the page. It goes against many of the oft-quoted best practises of modern content: they use statics over video, pictures are often landscape, and the captions are long, long, long — often spilling over into multiple posts. Each HONY story is a first-person narrative presented as a quote — often discursive, frequently both funny and profound — with a portrait photo. The format could not be simpler, and yet — ‘though much imitated — few have been able to focus on the subject’s humanity quite as well as the original. The secret is that there is a reason for each story. There is a kicker, a feeling that stays, as Wright Thompson says, in the hollow of your stomach at the end. There is a hammer. And you must protect the hammer.Sorry, that was a long one. To lighten the mood a little, here’s a quote from Blood Meridian:

“Men are born for games. Nothing else. Every child knows that play is nobler than work. He knows too that the worth or merit of a game in not inherent in the game itself but rather in value of that which is put at hazard. Games of chance require a wager to have meaning at all. Games of sport involve the skill and strength of the opponents and the humiliation of defeat and the pride of victory are in themselves sufficient stake because they inhere in the worth of the principals and define them. But trial of chance or trial of worth all games aspire to the condition of war for here that which is wagered swallows up game, player, all.”

Nothing really to add. Just always enjoyed that bit.Ultimately — and shouldn’t all part-tens of a ten-part essay be ultimate? — storytelling is about theme, not format. Fuck McLuhan. We decry the whittling down of our options to succeed — that writers must write about vapidity, that writers must make video, that videos must be dumb, that video must be short, etc — but aren’t we looking to achieve a sense of universality?

The personal essay boom (2008ish to 2016ish) told us something that I don’t think we really listened to. People want to read — or hear, or watch — stories about people. That’s all we really care about. Maybe we’re nosy, or maybe it’s the way we interact with the world, through connection with others.

The influencer/creator boom (ongoing, now seemingly eternal) tells us something, too. What a lot of writing has lost is its need to share. Influencers do nothing but share. They overshare. They tell-all. Fans become over-identified with these personalities because they identify with their themes. They buy what these people are selling because what they are selling is their theme.

We want to understand ourselves so we learn about other people, we listen to them speak, even if that’s their job: to speak and speak and speak. And yeah, some of it is dross, but much of it is not. We are a species who, for 95% of our history, has shared through oral traditions. Words spoken aloud are, after all, more accessible than those written down. What we dismiss now as navel-gazing, many many millions more understand as storytelling in its purest form.

Other writers who are very good at doing this, albeit at a far longer length: mid-century titans like Jospeh Mitchell, who wandered into house parties in New York and quarried perfect non-fiction short stories from what he found, and Charles Kuralt, whose nostalgic vignettes of the hard-scrabble Joe Public won him two Peabody awards; more recent examples in Eli Saslow, whose portraits of people surviving in “the fissures of post-pandemic America” won him a Pulitzer in 2023, and Gary Smith, probably the greatest sportswriter of all time, as well as our close personal friends Susan Orlean and Wright Thompson.