In 2022, I listened to whatever combination of songs was required to unlock recommendation after recommendation of what can only be described as “old Italian B-movie soundtracks”. Piero Umiliani, Carlo Savina, Fabio Fabor, a smattering of non-cowboy Ennio Morricone. Films with titles like Naked Girl Killed in the Park, School of Erotic Enjoyment, and Nine Guests for a Crime. OST’s packed with warbling synth notes, maudlin whistles, fuzzy harps, clip-clopping drums. What vocals present usually featured breathless women woozily singing non-words. I listened to a lot of it (Umiliani was my second-most listened to artist in 2022; his album La ragazza dalla pelle di luna my fourth-most listened to album) but there was a moment in early 2023, a whole year ago now if you can believe it, when I realised: I don’t think I actually like this music lol. It was simply present. It was just happening to me and I was letting it. Listening to all this music felt right in the moment—obscure enough to feel like a badge of honour, ambient enough to let permeate my every waking moment, making me feel like The World’s Smartest Man when I recognised Umiliani’s ‘Ricordandoti’ as the sample in Loyle Carner’s song ‘Ain’t Nothing Changed’—but was most of this music actually good? The algorithm suggested so. It suggested it as an offer to scratch the warm, fuzzy belly of my ego. The obsequious ego rolls over to oblige. Who am I to argue with computers?

For a book I’ve not yet read (because it comes out today!) Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture has been on my mind a lot. Writing about big ideas hiding in plain sight is (alongside grubby, ambiguous crime novels about bad guys killing badder guys) my favourite kind of writing and, for a decade, Chayka has had the market cornered. Most recently he has made the all-powerful algorithm his beat: not just how it exists in-app, but how it manifests IRL, too. I first noticed his work in his 2016 article on ‘AirSpace’—his name for the self-replicating AirBNB design aesthetic that has permeated our very idea of what constitutes good taste. He describes the design strategist Igor Schwarzmann noticing an aesthetic uniformity playing out in coffee shop interiors around the world, how “an affluent, self-selecting group of people move through spaces linked by technology,” Chayka writes, “particular sensibilities spread, and these small pockets of geography grow to resemble one another, as Schwarzmann discovered: the coffee roaster Four Barrel in San Francisco looks like the Australian Toby’s Estate in Brooklyn looks like The Coffee Collective in Copenhagen looks like Bear Pond Espresso in Tokyo. You can get a dry cortado with perfect latte art at any of them, then Instagram it on a marble countertop and further spread the aesthetic to your followers.”

When every spot’s ‘good interior design’ can still so easily be boiled down to a vibe-ticklist—fast wifi, racing green leather furnishings, worn-brass fixtures, marble counters abutting mid-century furniture, Illmatic on the speakers, spare white walls punctuated by exposed brickwork, an abstract painting of a negroni on a striped tablecloth1, and posters for Chungking Express and a Spanish-language variant of Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money—it inevitably leaves us with the question: How do we know our taste is really our own?Jazz is back. Which is fun. A sort of natural progression from the ‘Lofi beats to study and chill to’ era, presaged by the films of Damien Chazelle and now thankfully ensconced in a Bublé-less land, jazz is back, baby, and it is everywhere. Or at least that’s what my algorithm is suggesting, anyway. I’ve already been Wes Montgomery-pilled, but it’s great seeing a video like the below—a live 33-minute set from a golden-hour Malibu mansion by the Yussef Dayes Experience, fronted by saxophonist Venna, quite possibly the coolest man on the planet right now—getting a million-plus views on YouTube in two-ish months. Jazz’s trajectory from the coolest genre in the world to the least cool genre in the world to elevator music to the coolest genre in the world is a fascinating case study: it is a music which has always favoured innovation and creativity, favoured going left-field and reporting back, and that makes it a perfect foil for the internet. Tastemakers, curators, and creators associated with the sound have harnessed the new visual languages of the internet and riding the algo’s wicked waves without sacrificing the heart of the music they love. For a genre which was once seen as elitist and exclusionary, jazz is doing more than most to bring new fans—especially young ones—into the fold.

I mentioned it in passing last week, but Condé Nast made the decision to fold, like globs of cold butter rolled into waiting layers of pastry, Pitchfork into GQ. Inevitably, it has everyone thinking about the death of journalism again, and specifically the last call for criticism. Pitchfork was home to a lot of great writers, some magnificent features, and still the occasionally thought-provoking review, but the retconning of its legacy ignores the factors which have led to its demise. These are blames laid at the doors of decision makers, not creatives, but publications die when they do not evolve. Many die because they grow too bloated, too set in their ways; too immobile to pivot, greedily scoffing the last scraps of programmatic advertising dollars, and, in search of those waning dollars, send the quality plummeting in a race for the bottom of an already well-scraped barrel. It has happened countless times before and will no doubt happen again. Sports Illustrated just shuttered. One website blamed its downfall on its “embrace of [the] woke agenda”. But really the most famous sports magazine of all time never understood the internet, nor did it wish to. It seemed unbothered by the way the internet changed the way we spoke, the way we read, the way we think, the way we wish to commune and to communicate.

As Ryan Broderick noted on Twitter, Pitchfork was probably just months away from riding the full-scale indie-sleaze revival on TikTok which, had the platform’s strategy leant into the wind-change, could’ve seen the website’s popularity rocket back to its previous heights. Its owners lacked the foresight to even contemplate this outcome. SI shared similar affliction: Sports—like music—dominates the internet’s cultural output. But SI’s social media looked like any other: news-hooked graphics without any differentiating tone of voice or point of view. Better would have been to set its stall out—this is what we’re about and why; here is what we do and what we don’t do and why—while adopting a content funnel approach to embrace new mediums without losing its soul.

Top of the funnel, you have your short video hits: crafted cuts of video highlights designed for scale. “Snackable”. Mid-funnel: pivoting its famed proclivity for longform journalism to video essays or audio storytelling, both mediums which scratch the same itch as a 7500-word piece about Seve Ballesteros in a medium suited to more on-the-go audiences. Bottom of the funnel, you have content for the converted: longform articles, its honestly spellbinding archive of some of the best writing in any genre, and, finally, its magazine. But all of these moves required Sports Illustrated to have an angle, a view-point which makes it content speak to us on a level that goes beyond surface. Content that makes us feel seen, understood, enriched. Without that, they were fucked. Just another drop in the bucket. You cannot be a generalist anymore, even if you’re a famous generalist: you are forced to compete with millions of pages hunting along the same stretch of coastline, social-first publications with far lower overheads and way less skin in the game.

The only way you can compete is to know who you are, what you stand for, and be unafraid to move with the times.

The podcast Critics At Large, produced by the New Yorker, futzed with the still-warm ashes of criticism (which is, you might’ve guessed, their job). They exalted the form (all three hosts are, to be fair, exaltant critics in their own right) as the opposite of gatekeeping. This, they say, “dignifies the entire endeavour”. Their arguments were intellectual and emotional rigour. But, for me, there remained a shadow looming: as the hosts shared examples of exemplary criticism—notably those of the late New Yorker dance critic Joan Acocella, whose descriptions in the profile of Mikhail Baryshnikov I shall soon nick wholesale for an overwrought piece about a Crystal Palace winger or whoever—they pirouette around the way the internet has allowed everyone to be a critic. Whether or not you have the background, qualifications, or contacts to drum-up a fancy commission at a well-regarded publication, you can get your thoughts out there into the world. If they’re good, they land with an audience. If they’re really good—or, more to the point, are presented in the right way—they can shape the way our culture thinks about a subject forever.

On the podcast, the question is parried. A notion is offered that the job of a critic is to “think deeply” about a subject, maybe too deeply, and then present that subject as something more understandable, more meaningful than it was before. But that is not a job reserved for writers. There are lots of hundreds of writers who do this to an extremely high-level (for all the scaremongering, we may have never had quite as many smart writers writing smartly at the same time) but there are essayists on YouTube, Spotify, even on TikTok and Instagram Reels, who do the job just as well for a different kind of audience. But the medium remains the message.It’s now impossibly trendy for poptimists at publications-of-note to wax lyrical about the Real Housewives universe (RHU) and the like. It is writing about the low-class for the high-minded, written by people who should know better—which makes it oh-so-bloody-naughty, doesn’t it? But more pervasive than slumming is the idea that some mediums are inherently beneath others. Vertical video is, of course, the devil. Many “low” mediums are simply new mediums figuring out what they are for, and are looked down on as low-class mostly because, frankly, a lot of it is crap. But when we choose to focus only on the crap stuff, when we hate-share it, when we hold it up to the light to say ‘see this? this fucking thing? this fucking thing will kill us all’ and ‘we used to have books!’ the algorithm is trained to say ‘hey, everyone keeps sharing this thing: maybe people should see more of it’. Criticism is not objective. There is no such thing as high and low art: creation either speaks to us or it doesn’t. And there is no such thing as a high medium or a low one: we find the stories we are looking for.

I won’t dwell on the subject because, thankfully the discourse has already departed, but Saltburn is not a good film. It is, as one Letterboxd review describes it, “a movie about how Jacob Elordi is simply so fucking hot that his mere existence is enough to make someone legally insane”. But it’s also what happens when a filmmaker alludes to, but crucially does not interrogate, what they see. It is a gorgeously shot film about posh people created by one of the poshest people you can imagine that cannot cannot penetrate its own surface, even as its tumescent lead character writhes in a private graveyard and sodomises the sod in which the object of his obsession is buried. Saltburn is a film that cultivates mystery but abhors ambiguity. Every move is explained. Every jump-scare telegraphed. Like the abhorrent aristocrats who populate its titular mansion, it clambers for secrecy but cannot stop itself from blabbing. It does not gate-keep, but only because it does not trust its audience to follow. We get the art we’ve been told we deserve.

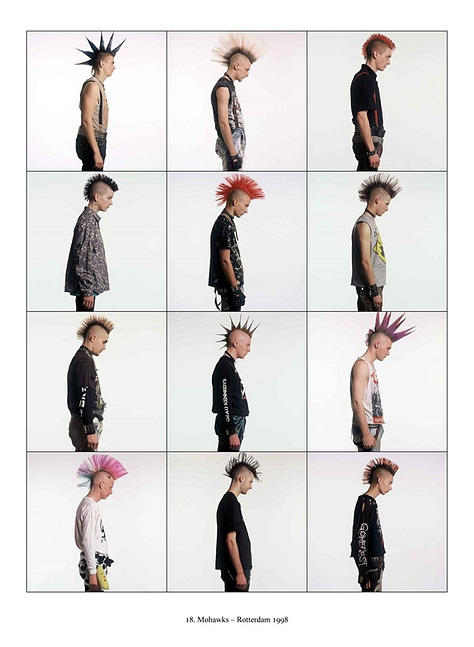

I recently rediscovered the work of Exactitudes, the Rotterdam-based art project that has been documenting subcultures across Europe through three-by-four grids of street-style photography since 1994. The social taxonomy rattles from fascinating to banal: there are goths and e-kids and gabber heads and American dads and French intellectuals and old men in lycra who are bang-into cycling. Subculture and sociology fascinates me, perhaps out of desperation as homogeneity spreads. The stories we tell ourselves and others through uniforms have always been an important part of youth culture, but consumerism has increasingly anaesthetised aesthetics and removed its vital subversive context. As you move backward in time through Exactitudes’ archive, it’s interesting just how normal everything looks.

“The difference between then and now is that now we live in a complete consumer culture,” Ari Versluid, the project’s co-founder, told Dazed. “Youth see themselves as global consumers and that is how they are addressed. There is such a shift of thinking that punks—even when they feel the same emotions of aggression—can’t express [themselves] in the same way now. The way we organise cities has changed. There are cameras everywhere. You can’t manifest yourself on the street. There are hardly any spaces where you don’t find places to consume.”

Samples from Exactitudes. One fascinatingly algorithim-less place I find myself more and more is Are.na, a Pinterest-style collage of inspirations. It’s an absolute fucker to navigate, but that’s part of the charm: it is a website that encourages spelunking; delving into its scattershot caves looking for something to pique your interest. Your search terms have to be either impossibly specific or wistfully vague. You may never find what it is you were looking for, but chances are you’ll stumble across something which may send you in a totally different direction, which is how the best of creativity works, I always think. I’ve recently had a hankering to start a magazine again and so, looking for a spark, tripped over this 26-year archive of scans of the unnecessarily stylish magazine Ministry, a publication created by a branch of the Seventh-day Adventist church. No need for it to look this cool, really.

Taste, as Kyle Chayka describes it to Ezra Klein in a recent podcast interview, “is knowing who you are and knowing what you like, and then being able to look outside of yourself, see the world around you, and then pick out the one thing from around you that does resonate with you, that makes you feel like you are who you are or that you can incorporate into your mindset and worldview…. It’s a process of collection, almost. Like you’re grabbing on to the little voices and artists and touchstones that make you who you are and give you your sense of self. You’re drawn to something without knowing why.”

His book Filterworld opens with a quote from Voltaire, a move that host Klein openly dismisses as cliché: “In order to have taste, it is not enough to see and to know what is beautiful in a given work. One must feel beauty and be moved by it.”

But first we have to find it.