Nostalgia in the age of loneliness

The streets won't forget. But that's because the streets don't exist.

First off, thanks for reading the last essay about The Bear (and the masculine habit of running around like a headless chicken at work) and for all the kind words. They mean a lot.

This essay… I mean, it’s all gotten a bit personal. It’s certainly been a way for me to work through some thoughts (and exorcise a few demons) about the way nostalgia is used by capitalism (and especially in football marketing) in an increasingly lazy way and why they keep getting away with it.

I hope this will be something people keep in their minds, maybe even refer back to, for a while; it’s been stuck in my head for years, and I’m glad it’s finally outta there. (I should also say: this also isn’t a dig at anyone specific. I think we’ve all been guilty in our own ways.)

Anyway, I hope you like it. I worked hard on it and even broke it up into little sections so you can go and have a breather. How thoughtful. So if you do like it, please hit that Like button on the Substack app or, on email, share it with some mates. I’d appreciate that.

All the best.

I.

“BIG Jim Traynor, a pint of beer at his elbow, settled down in a corner of a Liverpool tap room, opened a packet of crisps, and began to study an encyclopaedia,” reads the opening of an article in the Daily Mirror from July 1961. “Across the table, Charlie Vipond, from the local gasworks, eagerly flicked through the pages of Whitaker’s Almanack. ‘Hey, mate,’ he shouted, ‘what year did Henry VIII lop off Anne Boleyn’s head?’ No one batted an eyelid. It was just part of the latest pub craze… QUIZ MANIA.”

On a Tuesday afternoon, two summers before Vipond’s outburst, a meeting to start the first organised, recognised, competitive Quiz League was held at the Mount Hotel in Bootle.

Bootle: the birthplace of Jamie Carragher, Derek Acorah, and the pub quiz.

In October 1959, the league kicked off that October with ten teams taking part.

By October 1964, the Merseyside Quiz Leagues—now a combination of divisions (‘stretching from Southport to Speke’) organising general knowledge quizzes in a web of pubs, clubs and factory canteens—hosted over 4000 people cramming facts esoteric, abstruse, and downright obscure. The working class of the English north-west had begun a full-blown phenomenon, turning over the recherche and the recondite in their heads in the hope their time will come; in the hope of winning that most prized of possessions: A pint glass filled with shillings and the title of smartest bloke in the pub.

II.

I’ve been thinking a lot about nostalgia, memory, and the Illusory Truth Effect, the results of reiterating fake truths.

In 1977, three psychologists began studies to discover the power of fake truths. In their tests, forty college students were asked how certain they were that each of the sixty statements in front of them were true or false. Lists of statements were provided three times over the space of six weeks. Some statements were actually true, many others were plausibly false.

Each time a list was provided, forty of the statements changed and twenty statements, the false ones, were repeated. From the first session to the second, students became more certain that these incorrect, repeated statements must have been true. By the third session, nothing could change their minds.

Visual cues also undermine our ability to sniff out mistruths. In another study, researchers found that when statements were written in a lighter, hard-to-read colour, they were more often deemed more likely to be false than the same statements written in a darker, easier-to-read colour. It’s an effect known as ‘processing fluency’: in essence, the easier something is to understand, the more likely it is to be true.

These are relatively small studies, but this fluency speaks to the same primal psychology that drives brands to ‘blanding’—the idea that the more comprehensible your logo, the more trustworthy it seems—and politicians repeat their slogans and party lines again and again and again.

As a football fan, you see it every day.

‘The streets won’t forget’ is a phrase often trotted out by the loose-knit collection of Fantasy Premier League-addicted normies, sociopath trolls, and engagement farms known as ‘Football Twitter’ to describe a cult favourite footballer. To this day, ‘The streets won’t forget’ sets my teeth on edge. It’s undoubtedly effective: a phrase stolen from Black Football Twitter, evocative of everyday-fan appreciation of mercurial talents all but driven out of the upper echelons of the modern game. But its usage smacks of exactly the kind of analytics-baiting, lowest-common-denominator bollocks that has left once useful (even quasi-utopian!) social media platforms in tatters and a creative economy that stares—doped, doomed, twitching—into a future reduced to AI prompts and copy-and-pasted phraseology in place of genuine storytelling.

Those footballers the streets won’t forget are not made more special in the remembering. Rory Delap does not suddenly become more talented or interesting or successful. But dudes can literally just sit around and name old sports players and just have the best time. The trouble is, we aren’t interrogating why.

What do we hear in the phrase ‘the streets won’t forget’? We mourn the loss of collectivity.

III.

The story of nostalgia is pretty messy; appropriate for an emotion that warms the hearts as much as it leaves a lump in your throat. The word itself was first coined by a 17th-century Swiss Army physician who explained away ailments in his troops as a mere yearning for the Alps. The word itself comes, as always, from the Greeks: nostos, a longing for home, and algos, the pain that came with such thoughts. Nostalgia, it was believed, could cause nausea, loss of appetite, cardiac arrest, even death. The good doctor prescribed opiates, leeches, and, eventually, extended breaks in the mountains, hoping to bring his boys back from the brink with some fondue and a glimpse of the pale-pink face of the Weisshorn.

Even into the 20th century, nostalgia had been described by scholars as everything from ‘immigrant psychosis’ to a ‘mentally repressive compulsive disorder’. It represented a distinctly slippery grip of reality, said others, ‘closely related to the issue of loss, grief, incomplete mourning, and, finally, depression.’ More up-to-date research has attributed the feeling to ‘brain structures known to be engaged in self-reflection, autobiographical memory, emotion regulation, and reward processing’. But have we really learned more about the process or are we viewing nostalgia through rose-tinted glasses? The feeling—bittersweet when it hits—is now associated with increased optimism, inspiration, self-esteem, and overall feelings of purpose and youthfulness.

“Nostalgia compensates for uncomfortable states, [such as] people with feelings of meaninglessness or a discontinuity between past and present,” says Tim Wildschut1, Professor of Social & Personality Psychology at the University of Southampton. “What we find in these cases is that nostalgia spontaneously rushes in and counteracts those things. It elevates meaningfulness, connectedness, and continuity in the past.”

But nostalgia is a relatively recent sensation. It is accepted that our ancestors—even our recent ancestors, up until about two centuries ago—did not feel this way. Far more often than not, people lived where they were born, which was mostly where their families were born, which was mostly where their grandparents were born. Feelings of meaning, connection, and continuity were apparent every single day. You didn’t need to go looking. According to Gary Cross, cultural historian and author of Consumed Nostalgia: Memory In The Age of Fast Capitalism, until modernity, time ‘was experienced mostly as a cycle of seasons and festivals, disrupted only by war or catastrophe. With little movement or change, there wasn’t much to be nostalgic about.’

For the uptick in nostalgia, we can reasonably blame speed. Industrialisation brought sensational progress, but far faster than human brains were ever programmed to process. Mobility came at a rate unimaginable by previous generations. Such modernity led to a distaste for the slow, the traditional. But it made people scared, too.

“At first glance, nostalgia is a longing for a place,” writes Russian novelist and cultural theorist Svetlana Boym, “but actually it is a yearning for a different time: the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams.”

“Modern people discovered inexorable change,” writes Cross, “and tried to get the past back as possession.”

IV.

Football fans are sold on this all the time, in increasingly short timeframes: New kits released with forced narratives that point your eyes to archival design elements that simply are not there, celebrating important events they’ve rarely mentioned before, but will now mention at every opportunity. Such references, so the wisdom goes, seek to unite the ‘collective’ of the ‘football family’. To consolidate these narratives, we get set-dressing: visual cues that amount to a quick rustle through the dressing-up box, a grab-bag of references. It is nostalgia told through caricature.

‘You remember this’, they say. ‘This was the seventies. The eighties. The 90’s.’

It is fascinating how institutions can absorb critique—here, a longing for the past—and render it ineffective. But that isn’t to say that you can’t at least do it and for (mostly) the right reasons. Arsenal and Ajax are two clubs that have recently repackaged the past in a way which feels authentic. Its successes are not in meekly shoehorning-in iconography, but working its story backwards from fans, from legitimate cultures within its fandom, to produce stuff people actually want and tell stories they might reasonably recognise.

Even in hyper-stylised moments, football cultural storytelling still has to make sense. You should understand why this story is being told and why it is being told in this way. If we are told that ‘football is nothing without fans’ (a trademark of the Against Modern Football movement pre-pandemic, pilfered by the Premier League in Covid’s wake) then successful storytelling should reflect fan realities, as well as real fan fantasies2.

“So many shirt releases are accompanied by soulless PR drives which wax lyrical about the influence of a design,” says Phil Delves, football shirt collector, YouTuber, and all-round expert on such chemisery (chemise like ‘shirt’ in French, and misery as in—you get the picture). “But those influences demonstrate little connection to the past it is supposedly tapping into.”

“With nostalgia,” he adds, “brands signal to fans: ‘Look, this new thing is actually grounded in what you know and love.’ The actual design of the shirt might be largely divorced from its source of inspiration, but the forced narrative can (at least attempt to) act as a blanket from criticism.”

‘Remember when football was football?’ clubs ask, smiling, nodding to the kind of printed match-day programme they no longer produce, before placing their hand on your shoulder, levelling their head, and looking deep into the cool of your eyes. ‘Do not ask what football is now. Do not ask where we are now.’

Loneliness, Tim Wildschut told WIRED, is a key emotional trigger of nostalgia. Loneliness can be seen as a feeling that we are isolated or that we are missing out. Some academics have even suggested using nostalgia for psychotherapeutic ends.

In the past, as people came to grips with their burgeoning modernity, we handed things down. Furniture, jewellery, clothing, pictures of those we love and who loved us. Even the more ephemeral—well-worn anecdotes you knew every word, gesture, and dramatic beat of—had intense meaning. There were lessons to learn from what we handed down to future generations: culturally, aesthetically, emotionally. The word ‘heirloom’ comes from Middle English—a tool passed to one’s heirs. These were things that were useful, whether we understood it at the time or not. But thanks to planned obsolescence and multiplied by chronic media multitasking and a news cycle that injects pure cortisol into our emotion-registering limbic system, it is increasingly hard to hold onto our memories—figuratively and near-literally.

From Mattel raiding the archives for IP to turn into blockbuster movies to the illusory effect in football marketing, is it any wonder we are becoming even more susceptible to capitalism’s increasingly retrospective sentimentality?

V.

“It’s uncomfortable to admit this,” writes Chuck Klosterman, a cultural critic it’s often uncomfortable to admit you still enjoy, “but technology has made the ability to remember things irrelevant. Intellectually, having a deep memory used to be a real competitive advantage. Now it’s like having the ability to multiply four-digit numbers in your head—impressive, but not essential. Yet people still want to remember stuff.”

Our brains are made up of neurons. You’ll already know that, especially if you’re from Bootle. And these neurons, they talk to each other using electrical signals called ‘action potentials’. The protoplasmic protrusions that extend out from the neuron to receive those signals are called dendrites. The information received by the dendrites is interpreted by the cell body and shot along to neighbouring neurons through the wire-like axion. The axion is insulated by myelin, a white, fatty substance that keeps things on track. The more you repeat a signal—an action, a phrase, a baggy sentimentality dressed up as a loose collection of cultural touchstones—the more it increases myelin around the axion. Myelinated axons compose up your brain’s ‘white matter’ and complement its ‘grey matter,’ composed of neuron cell bodies. The better insulated the axion, the faster those signals fire around your brain.

The faster they fire, the better you’ll remember.

But what’s known as ‘chronic media multitasking’—the concurrent use of multiple streams of media, such as happens every single day of our lives—can irrevocably fuck with your brain’s cognition. Already linked to depressive symptoms and social anxiety, chronic multitasking has been linked to a reduction of grey matter density in the hippocampus, the seahorse-shaped component embedded deep into your temporal lobe, linked to learning and memory.

And so, as brains turn to mush from the forty-eight tabs you have open right now and the six WhatsApp groups you wish you could leave and the email you were supposed to send and that TV show you said you would watch and the football team whose off-season dealings you have damned yourself to follow with increasingly anaesthetic focus, it seems obvious that so much of our nostalgia—real or imagined—should play out online.

VI.

“Our representation of the past takes on a living, shifting reality,” writes Elizabeth Loftus, probably the most influential female psychologist of all time. “It is not fixed and immutable, not a place way back there that is preserved in stone, but a living thing that changes shape, expands, shrinks, and expands again, an amoeba-like creature with powers to make us laugh, and cry, and clench our fists… It has enormous powers—powers even to make us believe in something that never happened.”

VII.

In its current bloated state, modern football reflects our broader culture. According to Deloitte3, Europe’s ‘Top Five’ leagues made £17.2 billion in combined revenue in 2021/22. According to the Geneva Centre of Housing Rights and Evictions, sport is one of the biggest displacers of humanity, second only to war; impacts from its ‘sports mega events’ (World Cups, Olympics, etc) will cause over 500 million people to lose their homes in the next forty years. The progress of capitalism has left tastebuds singed, imaginations stunted, social media managers with PTSD. But it has also left us with a curious duality: Football is impregnable; often unbreachable, psychologically, philosophically, or even legislatively. Football, as a concept, probably by design, is too large to tackle as a whole. But even as its enormous wealth insulates from anything approaching introspection, it asks us to look back fondly on what has been lost, its arm around our shoulder, and suggest that we might want to commemorate this cultural forfeiture with a quick tour of the club shop.

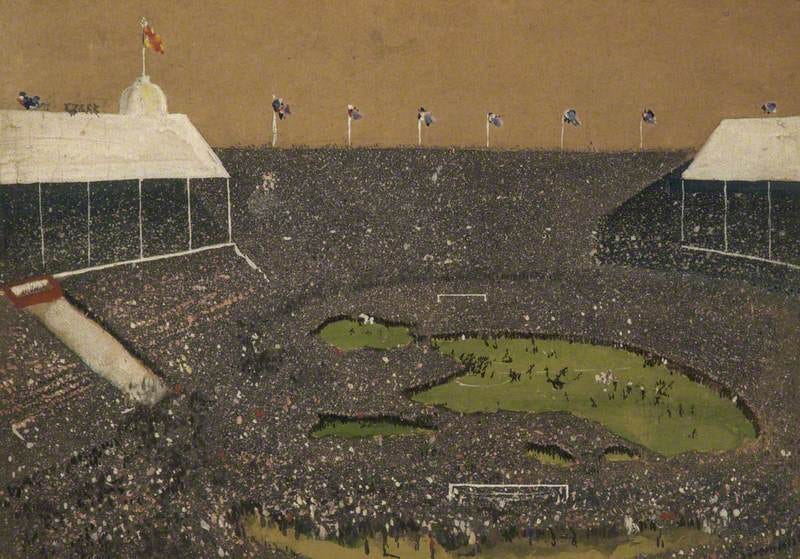

The gentrification of football has been damning. By ‘redeveloping’ football and its culture, the Premier League sought to create ‘a whole new ball game’. Its matches now have the most expensive tickets in the world. The quality of the play is without question, but what has been lost? Its clubs were once communal spaces. They represented railways and factories and social clubs. Institutions. Times change, of course. But people like to describe sports stadia as the ‘modern cathedral’. Places of worship for 'the common man. The heartbeat of the local area. They’re right, but not in the way they think. The cathedral is built at great expense. It is a vanity project to ideas. To the idea of hope, to the idea of ideas. But think of the other public meeting points we’ve lost to gentrification: shops, libraries, pubs; the human ecology of working-class streets. Now the only communal space is memory.

And, yeah, sometimes that’s in advertising4 because brands are the only people with budgets anymore, but that doesn’t mean it has to be bad, does it?

A move away from ‘nod-to-nostalgia-and-that’s-your-lot’ to ‘these are the communities that this club/brand/product/thing still represents, somehow, despite everything, and they are disappearing unless you take a second to appreciate them’ storytelling would at least attempt to redistribute marketing budgets back into the pockets of the people who support them. For every brand, football club, and product you can imagine: Those people exist. Those stories are out there! If you can be arsed.

But, until then, it’s no wonder we’re desperate for the collectivity that nostalgia—even the illusion of nostalgia—brings.

‘Look back in joy: the power of nostalgia’ by Tim Adams, The Guardian, 2014

An interesting example of the latter Man United’s recent shoot with Marcus Rashford. Inspired by a famous photograph of Allen Iverson, Rashford sat casually on a stool draped in flags from the stands while holding a bunch of roses loosely at his side. It is played like a dream sequence: mixing nostalgia of older, more modernist iconography (the flowers, the pose) alongside the distinctly postmodern (the iconic cultural reference (Iverson), checklist of the contemporary football shoot (replete with fourth-wall-breaking backdrop, the metal pole of the background frame visible to show us that we are actually in the middle of the Old Trafford pitch), etc. When played straighter, it does not work. I guess if you want to be a pretentious cunt about it, you can call it ‘metamodernism’. According to artist and critic Luke Turner, “metamodernism engages with the resurgence of sincerity, hope, romanticism, affect, and the potential for grand narratives and universal truths, whilst not forfeiting all that we’ve learnt from postmodernism.” The reason why the Rashford shoot works (in my opinion) is that it’s not trying to portray reality. It is a dream sequence. Maybe I’ll write about all this another time.)

Annual Review of Football Finance 2023, Deloitte

I’m sure everyone here has at least pretended to read Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism. I tried to read it to impress a woman I was dating once, which I believe is how the text was intended to be consumed.

this is great sam! Came back to this one as Im currently in the midst of writing a dissertation linking Boym's ideas on nostalgia with a Paolo Sorrentino film and Diego Maradona. Definitely agree nostalgia should be a cultural cradle of unity which binds people together (and gives them hope) rather than a mere "look at this playful spin on our retro 3rd kit from the '80s when we got to the semi of the cup". Every club seems to shoehorn a 'nod-to-our-heritage' line at every other comms moment. Will be interesting to see how or to where Everton pivot their storytelling in their post Goodison era..

really bloody good this